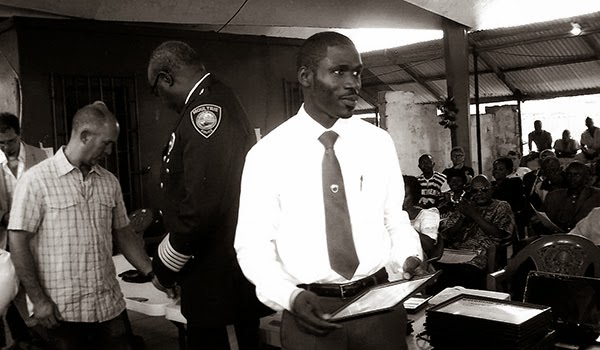

Benedict Dossen, a native Liberian and program administrator for

the Carter Center’s mental health work in Liberia, helps hand out

diplomas during the graduation of the fifth class of Carter

Center-trained mental health clinicians in August 2013. (Photo: The

Carter Center)

Story Source: The Carter Center Blog

Benedict Dossen, a native Liberian and an administrator for the

Carter Center’s Liberia Mental Health Program, explains what it is like

to watch and help his country heal.

Liberia is a West African country nearly the size of

Mississippi with a population of 3.8 million. But unlike many other

countries, Liberia only has one practicing psychiatrist. The need for

mental health services becomes even more pressing in the context of the

nation’s recovery from a brutal civil war spanning from the early 1990s

through 2003.

Like many of my Liberian colleagues, I have devoted my professional career to helping my nation rebuild.

We face many hardships living in a post-war country — from

unemployment to mental illness. I often think about the challenges

facing other young people today and find myself asking, “Why is the

world so tough?”

As an administrator for the Carter Center’s Liberia Mental Health

Program, I have seen first-hand how diagnoses and treatments can benefit

not just the patients, but the country as a whole.

Roughly 300,000 Liberians are thought to suffer from some type of mental

illness — with up to 40 percent believed to suffer from posttraumatic

stress disorder, alone, as a result of our civil war.

In Monrovia, Liberia’s capital city, I collaborate with many

partners, including the Liberia Ministry of Health and Social Welfare,

to expand access to mental health treatment for all those who need it

and to help train a new workforce of mental health clinicians.

To date, each of the 15 counties (similar to states) in Liberia has

trained clinicians, and eight counties have five or more clinicians.

These locally trained nurses and physicians assistants play an important

role in helping to integrate mental health care into primary care

systems and communities.

The most rewarding part of my work, however, is seeing the direct

impact increased access to mental health care has had on the Liberian

people. I once met a mother who brought her daughter to the clinic after

trying everything she knew to help her daughter’s serious mental

illness.

No traditional treatments, no number of prayers, and no amount of

help from her neighbors seemed to work on her daughter’s condition.

Yet, after seeking mental health treatment at their local clinic, the

daughter’s health improved drastically, so much so that she was hardly

recognizable to those who knew her.

This is what we work for. This is the example people need to see. If

we can help people address the issues that they have and get

rehabilitation, then those people can contribute back to their

communities.

Despite the significant challenges my nation faces, I believe there

is hope for Liberians facing mental illness. Even the staunchest critic

would agree that from one psychiatrist in Monrovia, alone, to 100 mental

health clinicians in all 15 counties with more to come — this is a good

bridge. This is increasing access.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment